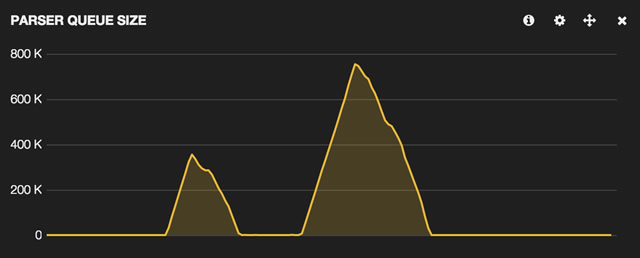

I've been doing quite a bit of work with the ELK stack (elasticsearch, logstash, kibana) through the logsearch project. As we continued to scale the stack to handle more logs and log types, we started having difficulty identifying where some of the bottlenecks were occuring. Our most noticeable issue was that occasionally the load on our parsers would spike for sustained periods, causing our queue to get backed up and real-time processing to get significantly delayed. We were able to see when our queue size was growing, but I needed to find better metrics which would demonstrate our real issue.

The Event Lifecycle

For non-trivial ELK stacks, there are typically a few services that a message hits between being a line in a log file and a plotted point on a Kibana graph. With logsearch, and logstash in general, those services are:

- The Shippers - are responsible for getting log messages into logsearch (e.g. tailing log files with nxlog) by pushing them to...

- The Ingestors - which listen for those messages on various ports for various protocols (e.g. syslog). Rather than trying to immediately parse messages and be a bottleneck, it pushes messages into...

- The Queue - which helps buffer against degraded performance from large spikes. In logsearch, this is redis. For real-time processing, the queue is typically empty because the messages should immediately be pulled by...

- The Parsers - which are responsible for parsing/extracting/transforming the log messages into something searchable. Typically, there are numerous parser rules for the various types of log files. Once parsed, they get pushed to...

- The Data Store - where the parsed message lives in elasticsearch for the rest of its life, searchable by tools like Kibana.

In our situation, we could see that the parsers were becoming the bottleneck. Despite relatively consistent logging rates, the CPU loads would max out and messages were reaching elasticsearch at very slow rates. As a short-term fix, we could easily start up several more parsers which helped a little bit, but this required manual intervention and wasn't actually fixing the problem.

Areas to Profile

Logstash itself has a --debug option which will dump details about every input, filter, and output each event

hits. This is helpful when testing individual events, but in a production environment with thousands of events per

minute it just became too noisy to be useful. We needed a different solution.

Typically, when all is said and done, we only have one timestamp to look at: @timestamp as extracted from the log

message and indicating when the log message was originally emitted. However, when the bottlenecks were occurring, there

was up to an hour delay between seeing the messages in dashboards and we had no way to measure how long messages were

stuck nor see where they were stuck. We decided to inject a few more fields into events...

First, we wanted to know when log messages were first entering our logsearch stack. This would help validate that our shippers are pushing data into the cluster in a timely manner (rather than significant batching or simply getting stuck). To do this, I configured ingestors to add the current time to every message when it came in. I also added fields documenting which BOSH job received the message to help us keep an eye on how balanced the ingestors may be. So, now our messages have a few additional fields...

@ingestor[timestamp]- the time the ingestor saw the event (e.g.2014-11-14T12:02:36.181Z)@ingestor[job]- the job which ingested the event (e.g.ingestor/1)@ingestor[service]- which logsearch job template received the message (e.g.syslog)

The next step in the lifecycle was the queue. The easiest way to monitor how long a message stayed in the queue is to add another timestamp right when the parser shifts the message off the queue. Since we have multiple parsers running, I configured them to also add their BOSH job name as a field. With the working theory that some of our parser rules were especially inefficient, I also added a final timestamp at the very end of the parsing rules. This would let us compare start/end parser timestamps. Now messages have a few more fields...

@parser[timestamp]- the time the parser saw the event (e.g.2014-11-14T12:02:36.450Z)@parser[job]- the job which parsed the event (e.gparser-z1/3)@parser[timestamp_done]- the time when the parser finished parsing the event (e.g.2014-11-14T12:02:36.462Z)

With those 6 new fields, the event now has some very valuable metadata that we can review. However, the information would be much more valuable if we could easily and aggregate and graph individual events. So I added a bit more overhead with math and graphable fields...

@parser[duration]- instead oftimestamp_done, switch to the duration the parser took (e.g.12)@timer[ingested_to_parsed]- essentially the time our logsearch stack spent on the event from when we first saw it to (roughly) when the end user should be able to search it (e.g.281)@timer[emit_to_ingested],@timer[emit_to_parsed]- if the conventional@timestampfield is parsed out of the log message, we can use that as an absolute starting point and get further insight into how slow shippers are to send the message (e.g.301,582)

Graphing Bottlenecks

After deploying the changes we were able to make some new Kibana dashboards to help visualize all our new metrics. Since parsers seemed to be the bottleneck, we first wanted to monitor how many messages the jobs were actually parsing at a given time...

During light loads where everything would be processing in real-time, we expected it to fully mirror our other chart measuring the rates we were receiving the messages...

Historically our spikes seemed random, so we started segmenting the average parse times by log types under the theory that some particular log was sending confusing messages. Our average time was around 10 ms, but after splitting by type we saw one log type was averaging more than one second (per message)...

Clearly this would cause all of our parsing to slow down whenever that log suddenly saw a lot of activity. Now that we

could find slow log messages, we were able to use them to track down some extremely non-performant regular expressions

in one of our grok filters. After deploying the updated filters, we started seeing much more consistent parsing

results among all our log types...

Conclusion

I learned a few things from all this. Most notably is how invaluable it is to be able to inject profiling into various steps of an otherwise unmeasured lifecycle. Obviously this adds a bit of processing and storage overhead into the stack, but since we haven't noticed a large impact in our day-to-day usage we've kept the extra profiling enabled. Although we have yet to experience another incident of a poorly performing parser, we're ready with metrics when we do. In the meantime, we use it to more easily monitor the practical capacity of our logstash components.

This became a great example about how such a relatively minor bug can be compounded and multiplied into bigger issues. A single log message taking 2 seconds isn't a big deal, even when you have 1000 other log messages/sec coming in - at worst you briefly lag by a couple seconds. If you have 10 parsers running it isn't even noticeable because the other 9 parsers pick up the slack. But if all of a sudden you get 100 log messages hitting the slow bug, those 10 parsers will each spend 20 seconds working through those slow messages and, once they finish those 100, there will be 20,000 messages waiting in the queue.

Whether it's the dashboards we use to self-monitor, the filters we build app-specific parsers of off, or this new profiling configuration that we were motivated to work on – I enjoy being in a role where these experiences can be codified, committed, and published in an open-source manner.

Reader Comments